Plant Identification Guide

If you’re going to forage, identify plants, or just know what you’re looking at in the woods, you need to understand leaves. Not just “it’s green and leafy” – you need to know the difference between opposite and alternate arrangement, simple and compound leaves, serrated and smooth margins.

This is foundational knowledge. Learn this once, and every plant identification gets easier.

Let’s break down leaf anatomy, types, shapes, arrangements, and margins so you can actually use this information in the field.

BASIC LEAF ANATOMY

Before we get into types, let’s define the parts:

BLADE: The flat, green part of the leaf (the “leaf” part)

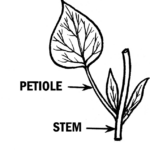

PETIOLE: The stalk that connects the blade to the stem (leaf stem)

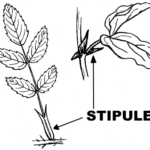

STIPULES: Small leaf-like structures at the base of the petiole (not all plants have these)

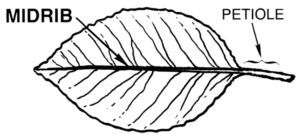

MIDRIB: The central vein running through the blade

VEINS: The network of vessels that transport water and nutrients

MARGIN: The edge of the leaf blade

APEX: The tip of the leaf

BASE: Where the blade meets the petiole

Why this matters: When you’re identifying plants, you’ll need to describe these parts accurately. “Sessile leaves” means no petiole. “Serrated margins” means toothed edges. Knowing the vocabulary makes identification possible.

SIMPLE VS. COMPOUND LEAVES

This is the first big distinction and where people get confused.

SIMPLE LEAVES

Definition: One blade per petiole. The leaf is in one piece.

What it looks like:

- Single, undivided blade

- May be lobed (like oak or maple) but still one continuous piece

- One petiole connects to stem

Examples:

- Oak (lobed but simple)

- Maple (lobed but simple)

- Sassafras

- Redbud

- Most single leaves you see

The test: Can you tear the leaf in half and both pieces have parts of the midrib? If yes, it’s simple.

COMPOUND LEAVES

Definition: Multiple leaflets on one petiole. What looks like multiple leaves is actually ONE leaf.

What it looks like:

- Multiple small blades (leaflets) along a central stalk

- Each leaflet may look like a small leaf

- But the whole structure is ONE leaf

Types of Compound Leaves:

PINNATELY COMPOUND:

- Leaflets arranged along both sides of central stalk (like a feather)

- Examples: Ash, Walnut, Hickory, Locust, Sumac

PALMATELY COMPOUND:

- Leaflets radiate from single point (like fingers on a hand)

- Examples: Buckeye, Horse Chestnut, some Lupines

BIPINNATELY COMPOUND:

- Twice compound – leaflets are themselves divided

- Examples: Honey Locust, Mimosa, Kentucky Coffee Tree

The Confusion:

How to tell if it’s compound or just a bunch of simple leaves:

- Find the bud – Buds appear at the base of leaves, not leaflets. If there’s a bud at the base of each blade, they’re separate simple leaves. If the bud is at the base of the whole structure, it’s one compound leaf.

- Check the arrangement – Leaflets on compound leaves are usually very regularly arranged. Separate leaves may be more irregular.

- Look at the base – Compound leaf leaflets often lack stipules. Simple leaves usually have them (if the species has stipules at all).

Why this matters: Ash and Boxelder both have compound leaves. If you count leaflets thinking they’re separate leaves, you’ll misidentify the plant. Always look for the bud.

LEAF ARRANGEMENT

How leaves attach to the stem is a critical identification feature.

ALTERNATE

Pattern: One leaf per node, alternating sides as you go up the stem

What it looks like:

- Leaves spiral up the stem

- Zigzag pattern

- Never two leaves directly across from each other

Examples:

- Oak

- Birch

- Willow

- Cherry

- Elm

- Most trees and plants (this is the most common)

OPPOSITE

Pattern: Two leaves per node, directly across from each other

What it looks like:

- Leaves in pairs

- Each pair is 90° rotated from the pair below (usually)

- Symmetrical

Examples:

- Maple

- Ash

- Dogwood

- Lilac

- Mint family plants

- Vervain

Memory trick for opposite trees: “MAD Horse” or “MAD Buck”

- Maple

- Ash

- Dogwood

- Horse Chestnut (or Buckeye)

Most trees are alternate. If it’s opposite, it’s one of a limited group.

WHORLED

Pattern: Three or more leaves per node, radiating from single point

What it looks like:

- Leaves in circles around stem

- Like spokes on a wheel

- Less common than alternate or opposite

Examples:

- Some Catalpa

- Joe-Pye Weed

- Some Milkweeds

- Bedstraw

BASAL ROSETTE

Pattern: Leaves all at ground level, radiating from center

What it looks like:

- Leaves in a circular pattern at base

- No leaves on stem (or stem leaves are different)

- Common in first-year plants

Examples:

- Dandelion

- Plantain

- Mullein (first year)

- Evening Primrose (first year)

Why arrangement matters: It narrows identification significantly. If you know a plant has opposite leaves, you’ve eliminated most species. This is one of the first things to check.

LEAF SHAPES

Leaves come in standard shapes that have specific names:

BASIC SHAPES:

LINEAR (GRASS-LIKE):

- Long and very narrow

- Parallel sides

- Much longer than wide

- Examples: Grasses, some Iris, Yucca

LANCEOLATE (LANCE-SHAPED):

- Narrow, tapering to point

- Widest below middle

- 3-6 times longer than wide

- Examples: Willow, Peach, some Hickories

ELLIPTIC (OVAL):

- Widest at middle

- Rounded at both ends

- 2-3 times longer than wide

- Examples: Many common leaves

OVATE (EGG-SHAPED):

- Widest below middle

- Rounded base, pointed tip

- Egg-shaped

- Examples: Lilac, Redbud

OBOVATE (REVERSE EGG):

- Widest above middle

- Pointed base, rounded tip

- Upside-down egg

- Examples: Some Magnolias

CORDATE (HEART-SHAPED):

- Heart-shaped with notched base

- Rounded lobes at base

- Examples: Redbud, some Violets, Catalpa

DELTOID (TRIANGULAR):

- Roughly triangular

- Examples: Some Poplars, Birches

ORBICULAR (ROUND):

- Roughly circular

- As wide as long

- Examples: Some Water Lilies, Nasturtium

LOBED SHAPES:

PALMATE (HAND-SHAPED):

- Lobes radiate from central point

- Like fingers on hand

- Examples: Maple, Sycamore, some Oaks

PINNATE (LOBED ALONG CENTRAL AXIS):

- Lobes along central axis

- Like feather

- Examples: Some Oaks (White Oak group)

Why shape matters: Combined with other features, shape helps narrow identification. “Opposite, heart-shaped leaves” is a much smaller group than just “heart-shaped leaves.”

LEAF MARGINS

The edge of the leaf is critical for identification.

ENTIRE (SMOOTH)

Description: Completely smooth edge, no teeth or lobes

What it looks like: Clean, unbroken edge all around

Examples:

- Dogwood

- Magnolia

- Rhododendron

- Sassafras (on unlobed leaves)

SERRATE (TOOTHED)

Description: Sharp teeth pointing forward (toward leaf tip)

What it looks like: Like a saw blade

Examples:

- Elm

- Cherry

- Birch

- Basswood

DOUBLY SERRATE: Teeth have smaller teeth on them (fine serrations on larger serrations)

Examples:

- Elm

- Hop Hornbeam

DENTATE (TOOTHED)

Description: Teeth pointing outward (perpendicular to edge)

What it looks like: Blunter than serrate

Examples:

- Some Oaks

- Chestnut

CRENATE (SCALLOPED)

Description: Rounded teeth

What it looks like: Scalloped edge, gentle curves

Examples:

- Some Mints

- Ground Ivy

LOBED

Description: Deep indentations creating distinct sections

What it looks like: Leaf divided into lobes

Examples:

- Oak (deeply lobed)

- Maple (palmately lobed)

- White Oak (rounded lobes)

- Red Oak (pointed lobes)

UNDULATE (WAVY)

Description: Gentle waves along margin

What it looks like: Rippled edge

Examples:

- Some Live Oaks

- Some Magnolias

Why margins matter: Margin type is often the deciding factor between similar species. White Oak (rounded lobes, smooth margins) vs. Red Oak (pointed lobes, bristle-tipped) – the difference is in the margins.

LEAF TEXTURE

GLABROUS: Smooth, no hairs

PUBESCENT: Covered with soft, short hairs

TOMENTOSE: Densely covered with matted woolly hairs

HIRSUTE: Covered with long, stiff hairs

SCABROUS: Rough to the touch (like sandpaper)

GLAUCOUS: Covered with whitish or bluish waxy coating

Why texture matters: Some plants are easily identified by feel. Mullein’s fuzzy leaves are unmistakable. Sassafras often has a slightly waxy feel.

LEAF VENATION

How veins are arranged:

PINNATE VENATION:

- One main vein (midrib) with smaller veins branching off

- Feather-like pattern

- Most common

- Examples: Oak, Cherry, most simple leaves

PALMATE VENATION:

- Multiple main veins radiating from base

- Hand-like pattern

- Examples: Maple, Sycamore

PARALLEL VENATION:

- Veins run parallel to each other

- Common in monocots

- Examples: Grasses, Corn, Lilies

Why venation matters: It’s a quick check for plant family. Parallel veins = probably a monocot (grass/lily family). Palmate veins in an opposite leaf = probably a Maple.

SPECIAL LEAF TYPES

NEEDLES:

- Evergreen conifers

- Thin, needle-like

- Examples: Pine, Spruce, Fir

SCALES:

- Tiny, scale-like leaves

- Overlap like shingles

- Examples: Cedar, Juniper

SUCCULENT:

- Thick, fleshy, water-storing

- Examples: Aloe, Sedum, Jade Plant

PUTTING IT ALL TOGETHER

When you’re identifying a plant by its leaves, go through this checklist:

- Simple or Compound?

- If compound, how many leaflets? Pinnate or palmate?

- Arrangement?

- Alternate, opposite, whorled, or basal rosette?

- Shape?

- Linear, lanceolate, ovate, cordate, etc.?

- Margin?

- Entire, serrate, dentate, lobed?

- Texture?

- Smooth, hairy, rough, waxy?

- Veins?

- Pinnate, palmate, or parallel?

- Petiole?

- Present or sessile (no petiole)?

- Long or short?

- Size?

- Measure length and width

- Color?

- Green, but what shade? Any variation top vs. bottom?

- Smell?

- Crush and smell – any scent?

Example Identification Process:

You find a plant. You check:

- Compound leaf with 5-7 leaflets arranged pinnately

- Opposite arrangement on stem

- Serrated margins

- Lanceolate leaflets

- No smell when crushed

This combination points to Ash (genus Fraxinus).

If it smells like garlic when crushed instead, it’s not Ash – you might be looking at compound leaves from something else entirely.

COMMON MISTAKES

Mistake 1: Counting leaflets as separate leaves

- Always look for the bud. Bud at base of whole structure = compound leaf.

Mistake 2: Confusing lobed with compound

- Oak leaves are deeply lobed but still ONE piece (simple). They’re not compound.

Mistake 3: Ignoring arrangement

- Arrangement is critical. Don’t skip this step.

Mistake 4: Not checking both sides of leaf

- Top and bottom can be very different colors/textures.

Mistake 5: Looking at only one leaf

- Check multiple leaves on the plant. Variation is normal, but the pattern should be consistent.

WHY THIS MATTERS

Learning leaf identification is not academic – it’s practical:

For Foraging:

- “Opposite, compound leaves with 5-7 leaflets” = narrowed down significantly

- Combined with other features, you can identify confidently

For Safety:

- Many toxic plants have distinctive leaf patterns

- Water Hemlock’s leaf veins end at notches, not tips

- This kind of detail saves lives

For Ecology:

- Understanding leaf types helps you understand plant relationships

- All plants in mint family have opposite leaves and square stems

- Patterns emerge

For Efficiency:

- Once you learn the vocabulary, identification guides make sense

- “Opposite, simple, entire margins, ovate” describes exactly one set of possibilities

FINAL THOUGHTS

Leaf identification is a skill that builds on itself. Learn the basics – simple vs. compound, arrangement, margins – and every plant you learn afterward becomes easier.

This isn’t trivia. This is the foundation of plant identification. Master this, and you’re no longer guessing. You’re observing, cataloging, and identifying with confidence.

Go outside. Pick a plant. Work through the checklist. Describe what you see using the correct terms. Do this enough times, and it becomes second nature.

And when someone asks “how did you know that’s an Ash?” you can say: “Opposite, pinnately compound, 5-7 serrated leaflets” – and they’ll know you actually know what you’re talking about.

That’s worth learning.

For plant-specific identification, see individual profiles in the Flora Archive. For dangerous look-alikes, see Deadly Doubles.